The structure of the Earth

The Earth is made up of four main layers, each with distinct characteristics:

- Inner Core: The innermost layer is solid and has a thickness of around 1,370 km. It consists of very dense materials, about five times denser than the rocks at the Earth’s surface.

- Outer Core: The outer core, which surrounds the inner core, is molten (liquid) and approximately 2,000 km thick.

- Mantle: The mantle lies above the outer core. A common misconception is that it is formed from molten rock. It is formed from solid, ductile rock and extends to a thickness of around 2,900 km.

- Crust: The Earth’s outermost layer is solid, with a thickness ranging between 10 km and 70 km. It is split into two main types:

- Continental Crust: Primarily made of granite and less dense than oceanic crust.

- Oceanic Crust: Mainly composed of basalt, making it denser than continental crust. The denser oceanic crust sinks beneath the continental crust when oceanic and continental crust collide.

Continental crust is much older and thicker than oceanic crust. It can be over 4 billion years old and is typically 30–70 km thick. In contrast, oceanic crust is younger, usually less than 200 million years old, and thinner, with a thickness of about 5–10 km. This difference is due to the constant recycling of oceanic crust at subduction zones and its formation at mid-ocean ridges, while continental crust remains more stable and less frequently recycled.

The lithosphere is the outermost rigid layer of the Earth, made up of the crust and the upper part of the mantle, while the asthenosphere is the ductile, semi-solid layer beneath it.

Plate tectonics

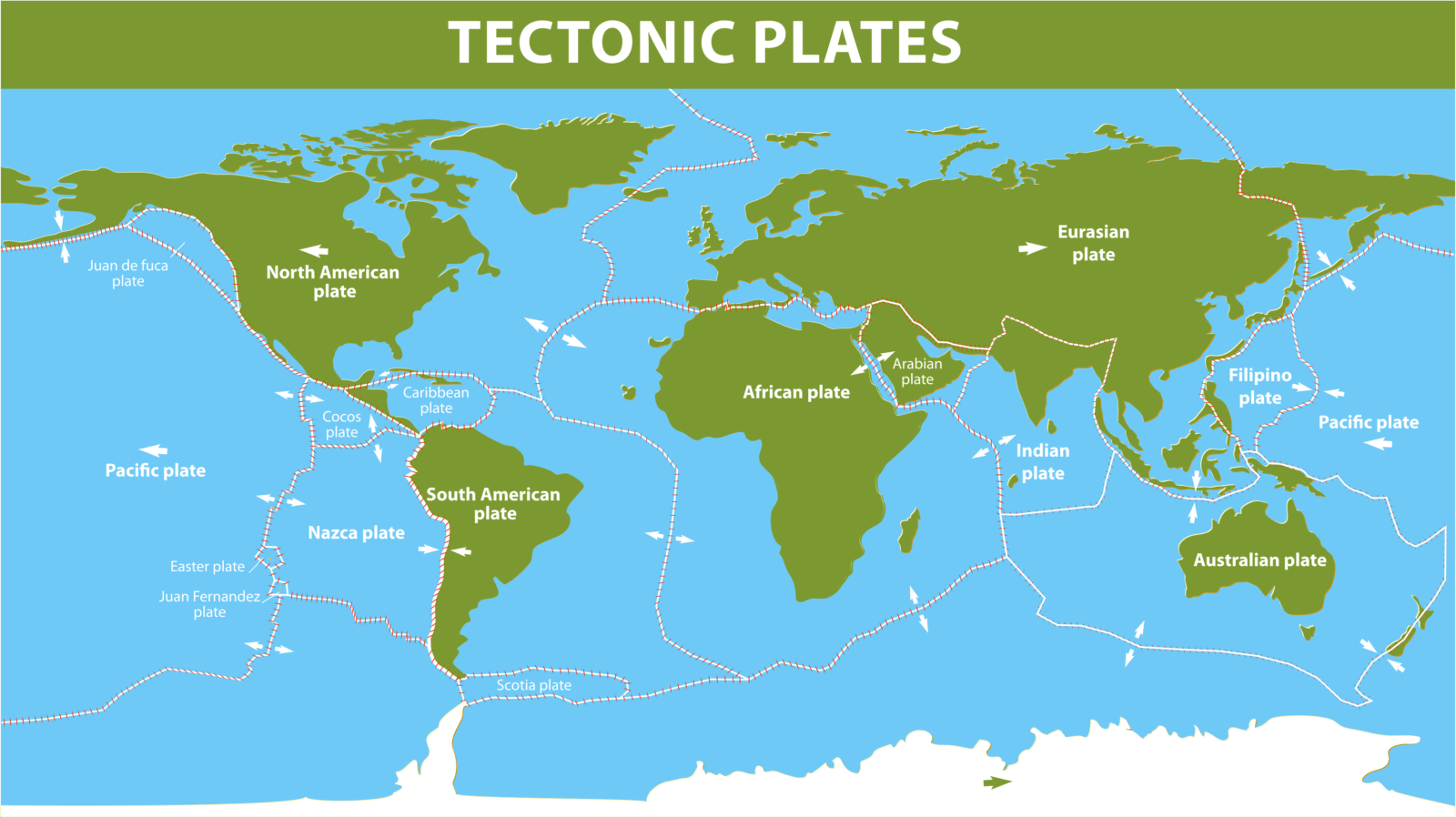

Plate tectonics is the theory that explains the movement of the Earth’s crust, which creates earthquakes, volcanoes, and major landforms. The Earth’s surface is divided into large, rigid pieces called tectonic plates that move slowly over time.

These plates sit on the asthenosphere, the solid but ductile upper layer of the mantle beneath the lithosphere. The material in the asthenosphere flows very slowly under pressure. Plate movement shapes the planet and is responsible for many of today’s natural hazards and landforms.

The theory of plate tectonics builds on the idea of continental drift, proposed by Alfred Wegener in 1912. He suggested that all continents were once joined together in a supercontinent called Pangaea before drifting apart.

Today, we know that the Earth’s lithosphere (crust and upper mantle) is broken into tectonic plates, which move due to forces acting within the Earth. This movement creates earthquakes, volcanoes, mountain ranges, and ocean trenches.

How do plates move?

There are several theories for the movement of tectonic plates:

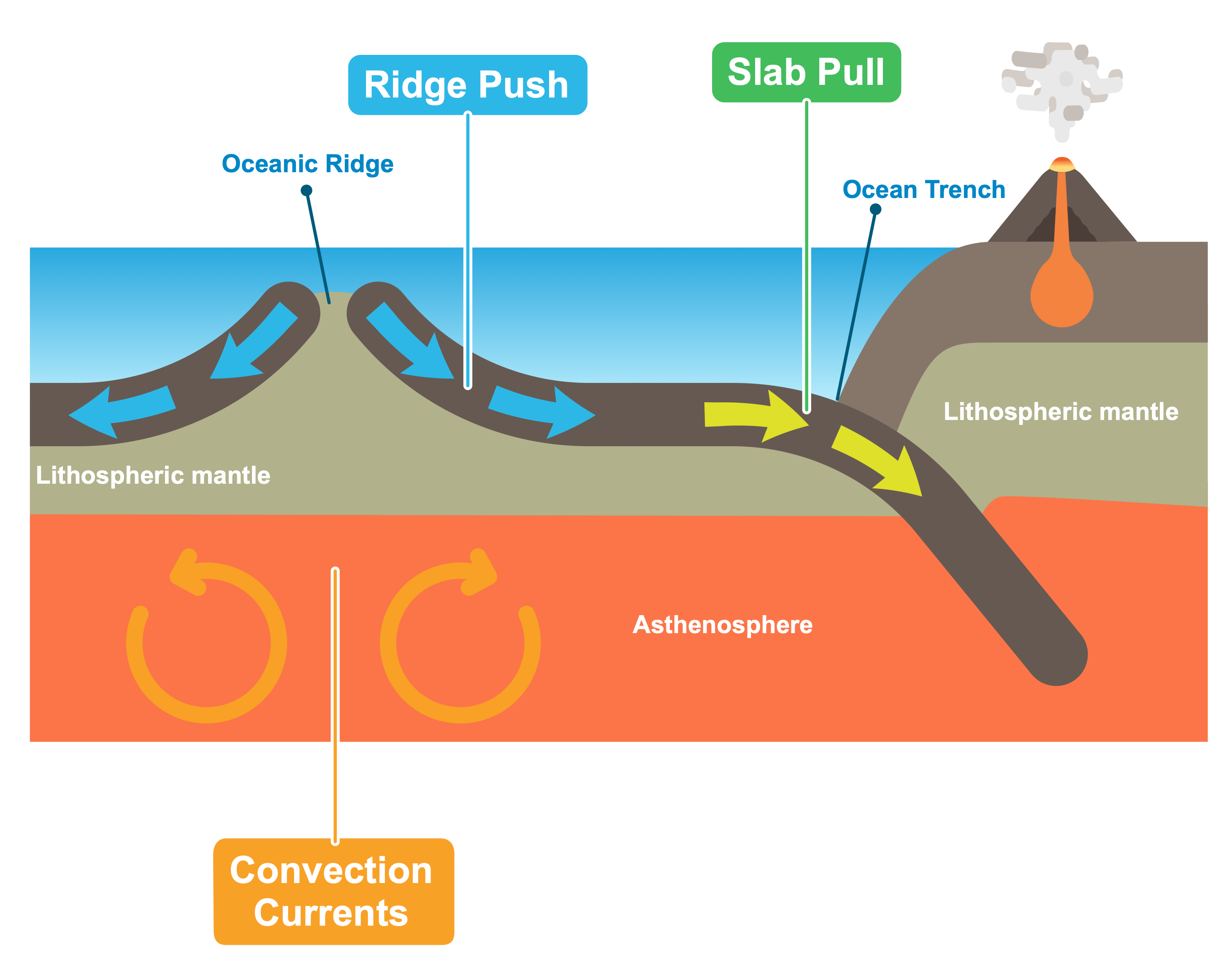

- Convection Currents (now largely discredited):

- Heat from the Earth’s core causes mantle material to rise, spread out, and sink, dragging the plates along.

- While this was an early explanation, it is now seen as insufficient to drive plate movement alone.

- Ridge Push:

- At constructive boundaries, magma rises to form new crust.

- The new crust cools, becomes denser, and slides away under gravity, pushing plates apart.

- Slab Pull (most widely accepted):

- At destructive boundaries, the denser oceanic plate sinks into the mantle during subduction.

- The sinking plate pulls the rest behind it, acting as a driving force for plate movement.

What are the different types of plate boundaries (margins)?

Plate boundaries are where tectonic plates meet and interact. There are four main types:

1. Constructive Plate Boundaries (Divergent)

- Plates move apart, creating space for magma to rise and form new crust.

- They occur mainly under oceans, forming mid-ocean ridges (e.g., the Mid-Atlantic Ridge).

- Key Features: Shield volcanoes, shallow earthquakes.

2. Convergent Plate Boundaries (Destructive)

- An oceanic plate collides with a continental plate.

- The denser oceanic plate is subducted (forced beneath) into the mantle, forming a subduction zone.

- Key Features: Ocean trenches, composite volcanoes, strong earthquakes.

- Example: The Andes Mountains in South America.

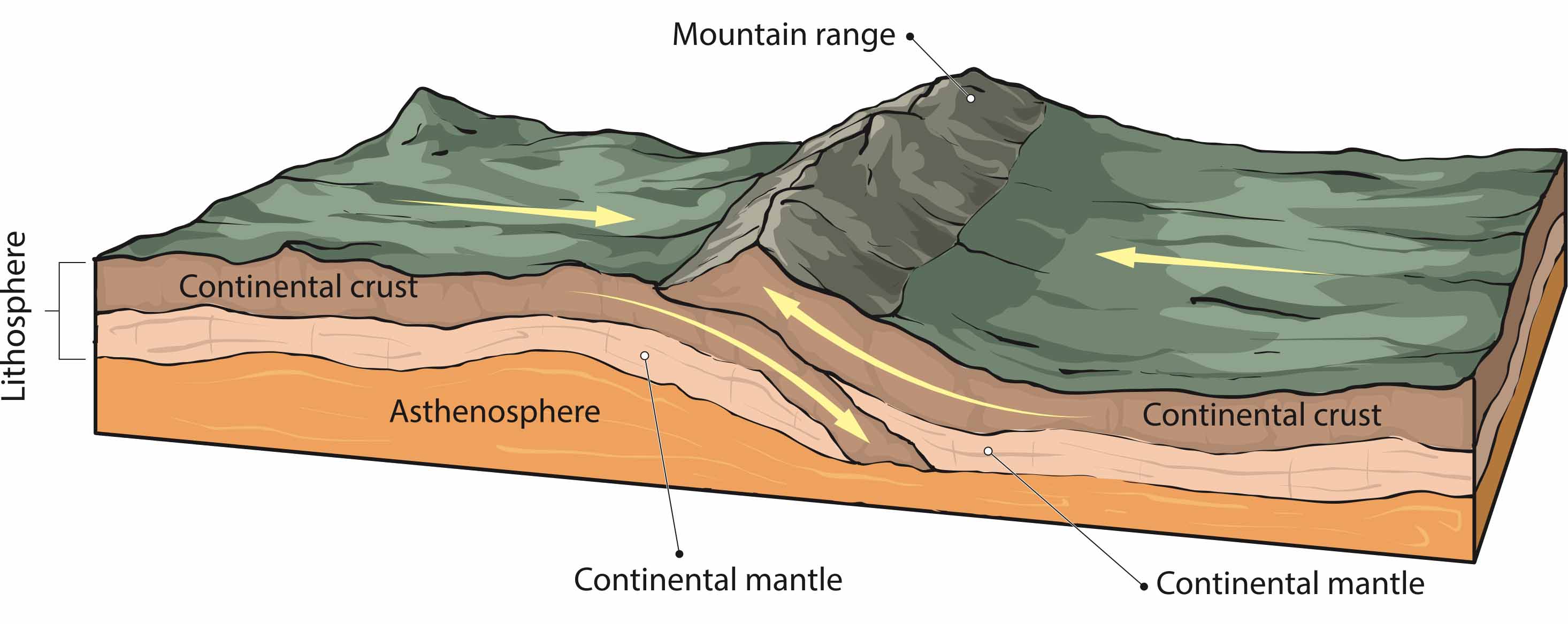

3. Convergent Plate Boundaries (Collision)

- They occur when two continental plates collide.

- Because neither plate can sink because they are similar in density, the crust is forced upwards, forming fold mountains.

- Key Features: Mountain ranges (e.g., Himalayas), shallow earthquakes.

4. Conservative Plate Boundaries (Transform)

- Plates slide past each other horizontally at different speeds or directions.

- No crust is created or destroyed, but friction causes earthquakes when the plates suddenly release energy.

- Key Features: Fault lines (e.g., the San Andreas Fault in California).

Characteristics of earthquake hazards

What is an Earthquake?

An earthquake is the sudden and violent shaking of the Earth’s surface caused by the release of built-up pressure within the Earth’s crust. This occurs when stress along fault lines or plate boundaries causes rocks to fracture and release energy in the form of seismic waves.

- Earthquakes are sudden and often last only a few seconds to minutes.

- Low-magnitude earthquakes happen frequently, while high-magnitude earthquakes are rarer but more destructive.

- Earthquakes often occur at plate boundaries, but they can also happen in areas far from boundaries due to stress within plates or human activity such as mining, fracking, and dam construction.

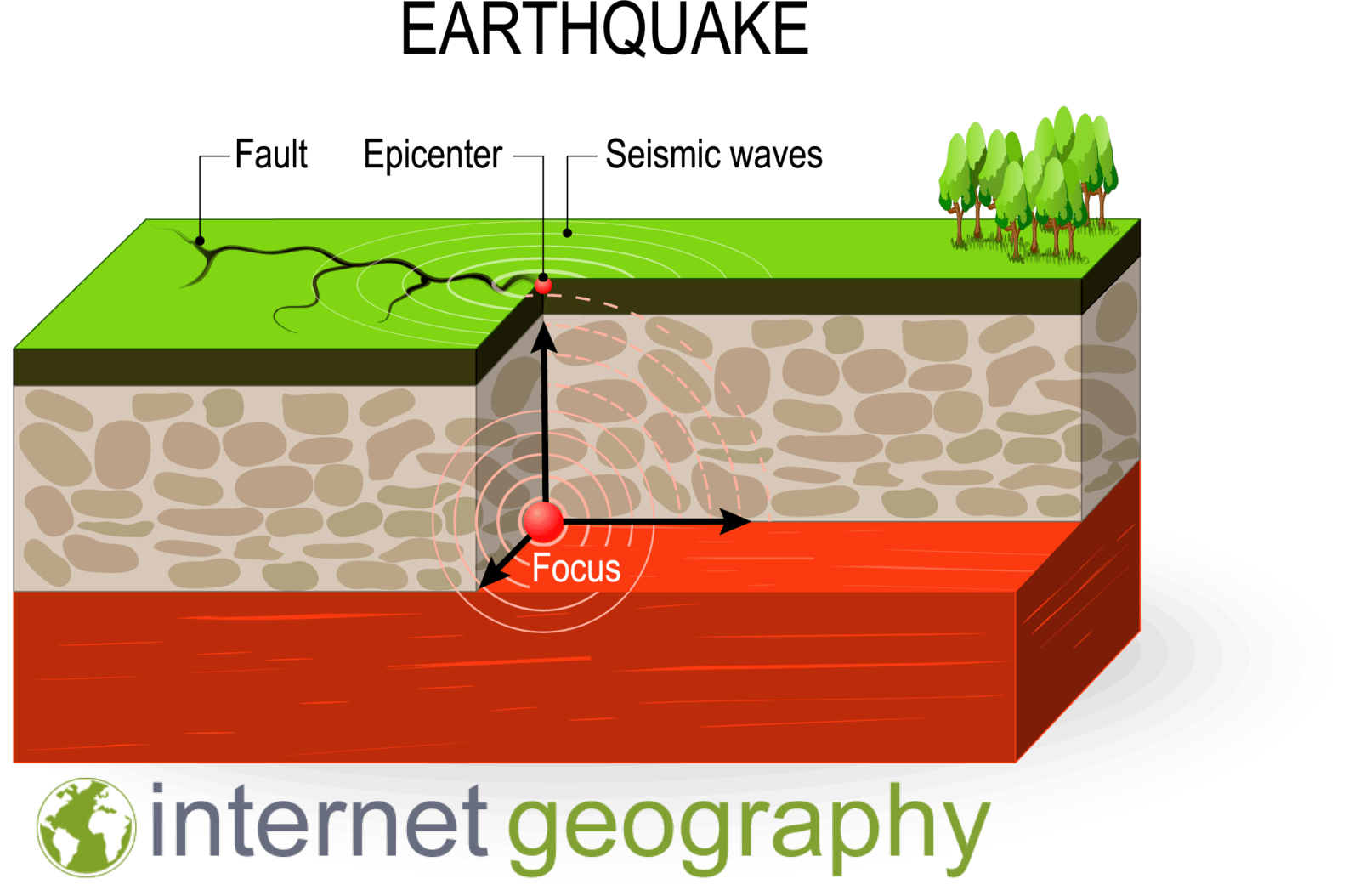

Focus and Epicentre

- The focus is the point deep underground where the earthquake starts and seismic energy is released.

- The epicentre is the point directly above the focus on the Earth’s surface, where the shaking is usually strongest.

The depth of an earthquake’s focus can be classified as:

Shallow Focus (0–70 km deep):

- Found at constructive and conservative boundaries.

- These earthquakes are more common and cause greater damage due to their proximity to the surface.

Intermediate Focus (70–300 km deep):

- Typically occur at subduction zones, where one plate sinks beneath another.

Deep Focus (over 300 km deep):

- Associated with subduction zones, often found where oceanic plates descend into the mantle.

- The energy dissipates as it travels, so deep-focus earthquakes tend to be less destructive.

Global Distribution of Earthquakes

Earthquakes are not evenly distributed across the globe. Most occur along the boundaries between tectonic plates, where plates move against, apart, or past one another.

- Linear Patterns: Earthquakes often occur in long, narrow belts along plate boundaries.Example: The Pacific Ring of Fire, a zone of intense seismic and volcanic activity.

- Away from Boundaries: Some earthquakes occur far from plate boundaries. These may be caused by stresses within a plate (intraplate earthquakes), such as those in the mid-western USA.

Sensitive instruments record around 500,000 earthquakes each year, though only a fraction of these are strong enough to cause noticeable damage.

Measuring Earthquakes

Richter Scale

- Developed in 1935 by Charles Richter, this scale measures an earthquake’s magnitude (strength).

- The scale is logarithmic: each whole number increase represents a tenfold increase in ground movement and 32 times more energy released.

- Earthquakes are recorded using a seismometer and displayed as wave patterns on a seismograph.

Mercalli Scale

- A subjective scale that measures the intensity of an earthquake based on observable effects (e.g., damage and human experiences).

- Ranges from I (barely felt) to XII (total destruction).

- Useful for gathering information from eyewitnesses but lacks scientific precision.

Moment Magnitude Scale (MMS)

- A modern scale used by scientists to measure the total energy released during an earthquake.

- It is more accurate than the Richter Scale, especially for large earthquakes.

- Each increase of 1.0 represents 32 times more energy released, and an increase of 0.2 means a doubling of energy.

Key characteristics of earthquakes

- Magnitude: The strength of an earthquake, measured on a scale like the Richter Scale or MMS.

- Frequency: Small earthquakes occur more often than large ones, which are rare but destructive.

- Duration: Earthquakes are typically short-lived, though aftershocks can continue for days or weeks.

- Impact Area: Higher magnitude earthquakes affect larger areas, while lower magnitude earthquakes have more minor, localised impacts.

- Human Activity: Activities such as mining, reservoir construction, and hydraulic fracking can trigger earthquakes, even in areas not prone to seismic activity.

Volcanic Hazards

What is a Volcano?

A volcano is an opening in the Earth’s crust through which magma, ash, and gases are released during an eruption. Magma is molten rock inside the Earth, and once it reaches the surface, it is called lava. Volcanoes form in specific locations, mainly at plate boundaries or hotspots.

Types of Volcanoes

The shape and type of a volcano depend on the lava it produces and the plate tectonic setting:

Shield Volcanoes:

- Formed by runny, basaltic lava that flows easily.

- They have gentle, sloping sides due to the spread of lava over large areas.

- Found mainly at constructive plate boundaries and hotspots.

- Example: Mauna Loa in Hawaii.

Composite (Cone) Volcanoes:

- Made up of alternating layers of ash, lava, and rock from repeated eruptions.

- They form steep-sided cones due to thick, acidic lava that flows slowly.

- Typically found at destructive plate boundaries where subduction occurs.

- Example: Mount Fuji in Japan, Mount Etna in Italy.

Hotspot Volcanoes:

- Hotspots are areas of intense heat in the mantle where magma rises to the surface, forming volcanoes.

- Unlike plate boundary volcanoes, hotspots occur in the middle of tectonic plates.

- Plates moving over hotspots form volcanic island chains, like the Hawaiian Islands.

Volcanic Activity

Volcanoes are classified based on their level of activity:

- Active Volcanoes: Erupt frequently or show signs of potential eruption. Example: Mount Pinatubo, Philippines.

- Dormant Volcanoes: Have not erupted for centuries but may erupt again. Example: Mount Rainier, USA.

- Extinct Volcanoes: Have not erupted for thousands of years and are unlikely to erupt again. Example: Mount Kilimanjaro, Kenya.

Global Distribution of Volcanoes

Volcanoes are unevenly distributed across the world and are mainly found at plate boundaries:

- Destructive Boundaries: Subduction zones where oceanic crust sinks beneath continental crust, creating violent eruptions.Example: Mount St Helens, USA (Pacific Ring of Fire).

- Constructive Boundaries: Plates move apart, allowing magma to rise and form new crust.Example: Eldfell volcano, Iceland.

- Hotspots: Found away from plate boundaries, where magma plumes break through the crust.Example: Kilauea in Hawaii, Teide in the Canary Islands.

- The Pacific Ring of Fire is the most notable zone of volcanic activity, containing 75% of the world’s active volcanoes.

Measuring Volcanic Eruptions

The strength of volcanic eruptions is measured using the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI):

- VEI ranges from 0 to 8, based on the volume of material ejected, the height of the eruption column, and the damage caused.

- Large eruptions are classified as VEI 5 or higher. A VEI 8 eruption (supervolcano) can eject over 1,000 km³ of material.

Volcanic Hazards

Volcanoes produce a variety of hazards that can cause widespread damage:

Pyroclastic Flows:

- Fast-moving clouds of hot ash, gas, and volcanic rock.

- Temperatures can reach 700°C, and they travel at speeds of over 500 km/h.

- These flows destroy everything in their path and solidify into pumice when they cool.

- Example: Pyroclastic flows from Montserrat’s Soufrière Hills volcano.

Lahars:

- Fast-flowing mudflows made of volcanic ash mixed with water from rain, lakes, or melting snow.

- They travel down valleys and deposit thick layers of mud over low-lying areas.

- Example: Lahars caused by heavy rain following Mount Pinatubo’s eruption in the Philippines.

Ash Clouds:

- Fine volcanic ash that spreads over wide areas, damaging crops, polluting water supplies, and disrupting air travel.

Lava Flows:

- Molten rock that flows down the volcano’s slopes, destroying land and infrastructure but generally moving slowly enough for evacuation.