The Challenges Created by Urban Change in a Major UK City

Home > Manchester Case Study > How has urban change created challenges in Manchester?

How has urban change created challenges in Manchester?

Deprivation is the degree to which a community or individual is deprived of amenities and services. Deprivation can be measured by:

- education (no one in a household has at least level 2 education, and no one aged 16-18 years is a full-time student)

- employment (if any member, not a full-time student, is either unemployed or economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability)

- health (if any person in the household has general health that is bad or very bad or is identified as disabled)

- housing (if the household’s accommodation is either overcrowded, in a shared dwelling, or has no central heating)

Deprived communities often have high population densities, congested roads, few parks and shops, and experience high levels of unemployment and crime.

Urban Deprivation in Manchester

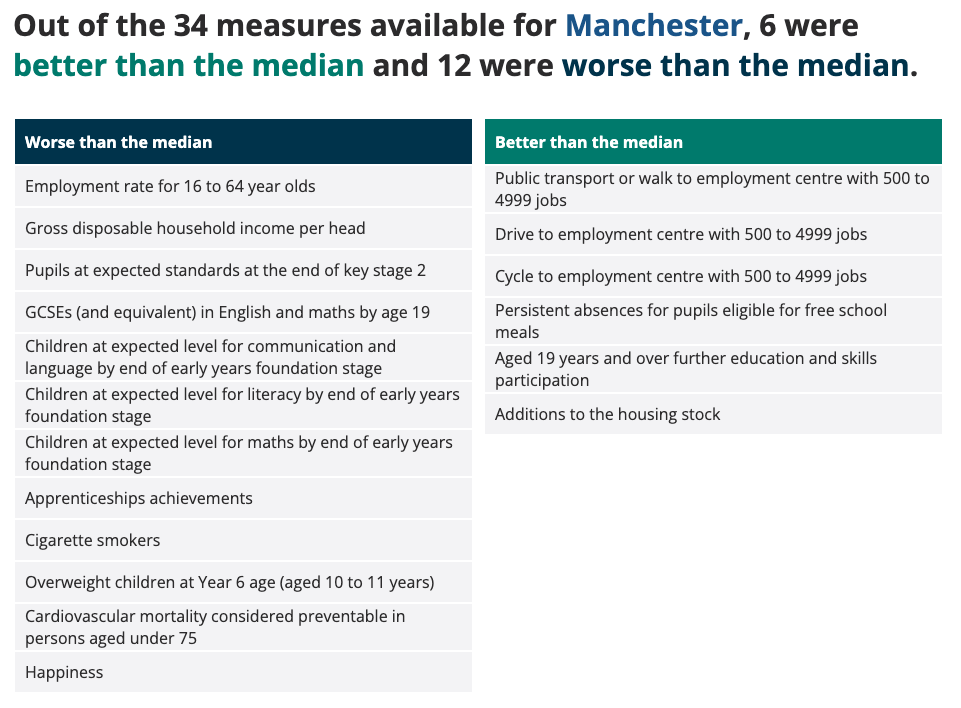

Deprivation Indicators for Manchester – Source: Office for National Statistics

Manchester is classed as the 6th most deprived place in the North-West. Of the core cities, only Birmingham ranks as more deprived than Manchester. 29.7% of Manchester’s children live in income-deprived families, which has decreased slightly since 2015. However, the most recent report is from 2019, and this figure is expected to be inaccurate due to the cost of living increases across the UK in 2022-2023. Greater Manchester Poverty Action suggests the % in 2022-2023 is perhaps more like 45%. The map below shows the boroughs of Oldham, Manchester Central, Blackley and Broughton, Bolton and Gorton as the six most deprived parts of the city.

The map below shows household deprivation in four dimensions (education, employment, health, and housing) in Manchester’s wards.

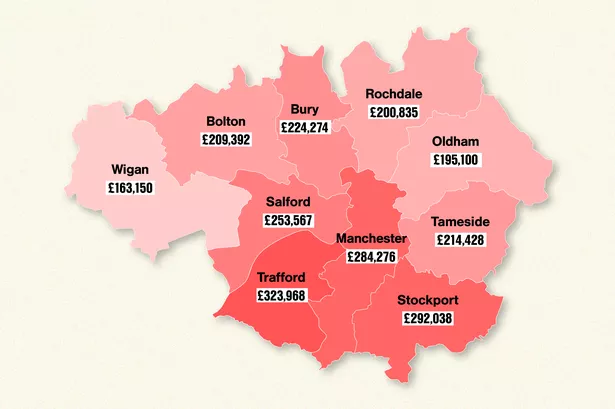

Inequalities in Housing

The demand for housing in Manchester has seen house prices rise significantly in the past 20 years, meaning lots of people have been priced out of the city. The average house price is now £295,700. However, there is significant variation across the city, with some city centre flats reaching over £3 million. The cheapest areas of the city to buy houses in are north Manchester. However, the recent boom in house prices has even made the cheapest houses and flats there over £175,000. There is a big north-south divide across the centre, with the average house price in Altrincham, South Manchester (£564,000) being almost triple that of Harpurhey, North Manchester (£143,000).

According to the 2021 Census, housing across Manchester is predominantly privately rented (32.5%). However, 28% is owned outright or via a mortgage, and 29.5% is social rent. The majority of housing across the city are semi-detached houses (31.9%), although terraced (28%) and flats (28%) are close behind.

Average house prices in Greater Manchester’s Boroughs – Source: Manchester Evening News

Inequalities in Education

Socio‐economic disadvantage in education is usually measured by eligibility for Free School Meals (FSM). Pupils are eligible for Free School Meals if their families are on low incomes and not working full-time. Greater Manchester has a higher proportion of children on FSM than England or the North West, with huge variations across the city. Stockport and Trafford have the lowest levels whereas, in the city centre itself, 1 in 3 children are on free school meals.

The map below provides an overview of educational attainment in local authorities in England and Wales based on the 2021 Census. By selecting Manchester, we can see an overview of the city.

Once selected, we can see that Manchester had a higher average qualification rank than 63% of local authorities. However, when you click on other areas within the area, you can see that areas such as Oldham, Rochdale and Tameside have a lower average qualification rank than approximately 85% of local authorities.

Trafford is the only borough in Manchester where over 60% of children achieve a ‘good level of progress’, compared to the city centre at 47.7% – the national average for England is 50.9%.

Inequalities in Health

Urban change has posed difficulties for the healthcare sector due to disparities in wealth throughout the city. The average life expectancy for women in Greater Manchester at 81.7 was lower than the average for England at 83.4 years. For men in Greater Manchester, the average life expectancy of 78.1 years was lower than the England average of 79.8 years. Only Trafford and Stockport had higher life expectancies than the average for both men and women in England.

The main causes of the differences in life expectancy are the biggest killers – heart disease, stroke, cancer and lung disease. In 2020 and 2021, deaths from Covid-19 also contributed significantly to the difference in life expectancy between the city’s most disadvantaged and most affluent areas. So we know that if we want to reduce health inequalities, we must prevent ill health and deaths from heart disease, cancer and lung disease. Smoking, unhealthy eating and lack of exercise are known to increase the risk of most preventable deaths from heart disease, lung disease, cancer and diabetes. These four conditions are responsible for most preventable deaths in Manchester. People with challenging social circumstances will find adopting and maintaining healthy habits or behaviours more difficult.

Inequalities in Employment

The map below shows the proportion of people economically inactive in Manchester’s local authorities. At the time of the 2021 Census, there are apparent differences between Manchester’s local authorities, with a more significant proportion of people in the north inactive compared to the south.

All of this data suggests that there is quite an apparent north-south divide across the city, with the most deprived being to the north of the city centre and the least deprived in the south.

Manchester’s Environmental Challenges

Urban change in Manchester has created a range of environmental challenges. These are mainly the result of Manchester’s rapidly growing population and changing industry. The challenges include:

- buildings used for industry becoming derelict

- new developments being constructed on brownfield and greenfield sites

- waste disposal

Dereliction

Manchester started to experience economic decline following the end of the Industrial Revolution. Once the factories closed, most of the inner city declined. Some of the old derelict mills have been converted into flats. However, there are still areas with vast amounts of dereliction. In the north of the city, where dereliction is high, the crime rate is also high, and vandalism and anti-social behaviour have increased.

Building on brownfield and greenfield sites

A brownfield site refers to land previously used for development, while a greenfield site signifies untouched land, usually on the outskirts of urban regions. Urban transformations such as deindustrialisation or the dismantling of substandard housing lead to the creation of brownfield sites. Preparing a brownfield site for redevelopment presents expensive challenges, such as waste clearance, land decontamination, and establishing contemporary infrastructure like water, electricity, and internet access. The Trafford Centre is an example of successful brownfield site redevelopment, transforming an old industrial warehouse into a multi-million-pound shopping centre. This area is continuously developing, with the planned development of the ‘Event City’ space into a new waterpark.

In 2019, Manchester City Council decided to dispose of 27 brownfield plots to open up the development of new affordable homes. Project 500 forms part of the council’s new housing strategy, which aims to deliver 10,000 affordable properties over the next decade. As land in the city centre is very high, Manchester City Council have started to eliminate greenfield and brownfield sites around the city’s edges to increase space for new houses. Although some of the houses built here are classed as affordable housing, many people who previously lived in the area can no longer afford to do so due to the high rent and house prices.

On the other hand, greenfield sites necessitate less preparation work, making them appealing to developers. However, greenfield developments often face opposition, and securing planning permissions can take considerable time. There haven’t been many examples of recent construction on greenfield sites in Manchester. However, some houses built on greenfield sites along the River Mersey have flooded numerous times in the last five years.

Greenfield sites around the city in places such as Cheadle, Sale, and Flixton are currently involved in conflict. Local people living in the area are contesting the proposal to build houses on these sites. In some places, trees have already been removed, which has caused local people to tie ribbons to the trees to show the council they are wanted.

Waste disposal

The pandemic has increased household waste in the city, which is reflected at a national level, where recycling rates reduced on average by 3.5% (Defra, 2021). Manchester’s recycling rate fell from 40.4% in 2019/20 to 36.6% in 2020/21. However, there has been a push to work together to ‘Keep Manchester Tidy’. Since 2019, there has been an overwhelming response from residents, young people, businesses, and partners – with more volunteers than ever organising clean-up events.

Recycle for Greater Manchester (R4GM) works with local councils across Manchester to inspire and encourage residents to manage their waste responsibly. It helps residents see the value of waste and the real benefits that can be achieved by wasting less, recycling more, and recycling right.

To reduce waste across the city, Manchester City Council has opened three ‘Renew’ shops. These shops sell pre-loved household items at an affordable price and are located at three of our recycling centres.

The shops stock various homeware, garden furniture, toys, sports equipment, books, etc. Items have been donated by residents and cleaned and repaired before being handpicked by staff for the shops in Eccles, Oldham and Altrincham.

The Renew shops aim to reduce waste, reuse unwanted items and increase recycling rates. Many of the items donated by residents would have otherwise gone to waste.

How has Manchester’s urban growth led to urban sprawl?

The outward physical growth of a city is known as urban sprawl. In Manchester, it has led to the city’s expansion towards the south and north. For example, the already somewhat built-up more desirable towns in the south of Manchester, such as Altrincham and Hale, have expanded further outwards towards Broadheath and to the north, areas in Bury have seen the most significant increase of new housing built.

Several factors in Manchester have contributed to urban sprawl as a result of urban change:

- The city’s rapidly growing population, primarily driven by migration from within the UK and overseas

- The scarcity of affordable housing in the city centre

- A competitive demand for land on brownfield sites in the city centre (for industrial, retail, and office uses) led to a steep rise in land prices

- Upgrades to transport infrastructure, facilitating easier commuting into the city centre

- Many people prefer to reside in quieter, less polluted semi-rural areas.

Manchester’s population is predicted to grow by 10% over the next 20 years, requiring around 179,000 new homes in the region by 2037. Because land in the city is so expensive, new homes must be built on the outskirts of the city centre.

What is the impact of urban sprawl on the rural-urban fringe?

The construction of extensive housing estates, motorways, and service infrastructure at the rural-urban fringe has sparked controversy. Residents and environmentalists have expressed worries about the loss of rural landscapes and the effects on wildlife biodiversity and habitats. Increasing traffic congestion levels, noise, and air pollution are also areas of concern. This has been of particular concern recently with the proposed development of the Manchester section of HS2 (now ‘cancelled’ – October 2023).

Manchester’s roads are some of the most polluted in the country. The Clean Air Zone is a plan to tackle pollution on local roads to protect health, jobs, livelihoods, and businesses.

Like many areas across the country, Greater Manchester has illegal levels of air pollution on some local roads. Poor air quality affects everyone’s health, particularly the most vulnerable. That includes deprived communities, children, elderly people and those with chronic conditions like asthma, heart disease, stroke and some cancers. It contributes to nearly 1,200 premature deaths in Greater Manchester every year. The Clean Air Zone is currently ‘on hold’ because the pandemic resulted in significant vehicle supply chain issues, rising vehicle prices, and a cost-of-living crisis. The original Clean Air Plan was no longer the right solution and could have caused significant financial hardship.

The growth of commuter settlements

Commuter settlements refer to areas where many residents travel to work in different locations. In the case of Manchester, the city sees more incoming commuters for work than those leaving for jobs elsewhere. While many commuters reside in the immediate rural-urban fringe, due to the success and expansion of the Metrolink, people from towns such as Altrincham, Bury and Oldham can all commute much more easily into the city centre.

Altrincham is an example of a commuter settlement. Its location along the Metrolink has meant easy travel into the city centre. However, this has pushed up house prices in the town and made it one of the most desirable parts of the city. This has also increased congestion on the local roads. People living further outside of the town on the rural-urban fringe then drive into Altrincham to get public transport into the city centre.

Unemployment has decreased across Manchester in the past year, from 7.1% in March 2022 to 5.8% in March 2023. Following the pandemic, residents from more disadvantaged communities have been impacted by a lack of skills, access to technology, and support to start and sustain learning. Therefore, a significant gap has been opened between the least and most deprived areas.

Quiz

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.