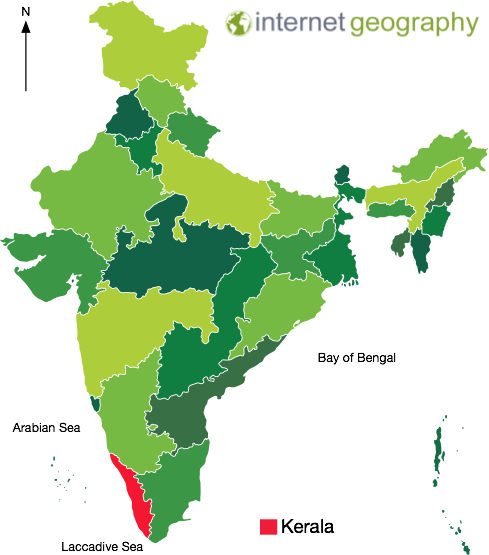

Kerala flood case study

Kerala is a state on the southwestern Malabar Coast of India. The state has the 13th largest population in India. Kerala, which lies in the tropical region, is mainly subject to the humid tropical wet climate experienced by most of Earth’s rainforests.

A map to show the location of Kerala

Eastern Kerala consists of land infringed upon by the Western Ghats (western mountain range); the region includes high mountains, gorges, and deep-cut valleys. The wildest lands are covered with dense forests, while other areas lie under tea and coffee plantations or other forms of cultivation.

The Indian state of Kerala receives some of India’s highest rainfall during the monsoon season. However, in 2018 the state experienced its highest level of monsoon rainfall in decades. According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), there was 2346.3 mm of precipitation, instead of the average 1649.55 mm.

Kerala received over two and a half times more rainfall than August’s average. Between August 1 and 19, the state received 758.6 mm of precipitation, compared to the average of 287.6 mm, or 164% more. This was 42% more than during the entire monsoon season.

The unprecedented rainfall was caused by a spell of low pressure over the region. As a result, there was a perfect confluence of the south-west monsoon wind system and the two low-pressure systems formed over the Bay of Bengal and Odisha. The low-pressure regions pull in the moist south-west monsoon winds, increasing their speed, as they then hit the Western Ghats, travel skywards, and form rain-bearing clouds.

Further downpours on already saturated land led to more surface run-off causing landslides and widespread flooding.

Kerala has 41 rivers flowing into the Arabian Sea, and 80 of its dams were opened after being overwhelmed. As a result, water treatment plants were submerged, and motors were damaged.

In some areas, floodwater was between 3-4.5m deep. Floods in the southern Indian state of Kerala have killed more than 410 people since June 2018 in what local officials said was the worst flooding in 100 years. Many of those who died had been crushed under debris caused by landslides. More than 1 million people were left homeless in the 3,200 emergency relief camps set up in the area.

Parts of Kerala’s commercial capital, Cochin, were underwater, snarling up roads and leaving railways across the state impassable. In addition, the state’s airport, which domestic and overseas tourists use, was closed, causing significant disruption.

Local plantations were inundated by water, endangering the local rubber, tea, coffee and spice industries.

Schools in all 14 districts of Kerala were closed, and some districts have banned tourists because of safety concerns.

Maintaining sanitation and preventing disease in relief camps housing more than 800,000 people was a significant challenge. Authorities also had to restore regular clean drinking water and electricity supplies to the state’s 33 million residents.

Officials have estimated more than 83,000km of roads will need to be repaired and that the total recovery cost will be between £2.2bn and $2.7bn.

Indians from different parts of the country used social media to help people stranded in the flood-hit southern state of Kerala. Hundreds took to social media platforms to coordinate search, rescue and food distribution efforts and reach out to people who needed help. Social media was also used to support fundraising for those affected by the flooding. Several Bollywood stars supported this.

Some Indians have opened up their homes for people from Kerala who were stranded in other cities because of the floods.

Thousands of troops were deployed to rescue those caught up in the flooding. Army, navy and air force personnel were deployed to help those stranded in remote and hilly areas. Dozens of helicopters dropped tonnes of food, medicine and water over areas cut off by damaged roads and bridges. Helicopters were also involved in airlifting people marooned by the flooding to safety.

More than 300 boats were involved in rescue attempts. The state government said each boat would get 3,000 rupees (£34) for each day of their work and that authorities would pay for any damage to the vessels.

As the monsoon rains began to ease, efforts increased to get relief supplies to isolated areas along with clean up operations where water levels were falling.

Millions of dollars in donations have poured into Kerala from the rest of India and abroad in recent days. Other state governments have promised more than $50m, while ministers and company chiefs have publicly vowed to give a month’s salary.

Even supreme court judges have donated $360 each, while the British-based Sikh group Khalsa Aid International has set up its own relief camp in Kochi, Kerala’s main city, to provide meals for 3,000 people a day.

In the wake of the disaster, the UAE, Qatar and the Maldives came forward with offers of financial aid amounting to nearly £82m. The United Arab Emirates promised $100m (£77m) of this aid. This is because of the close relationship between Kerala and the UAE. There are a large number of migrants from Kerala working in the UAE. The amount was more than the $97m promised by India’s central government. However, as it has done since 2004, India declined to accept aid donations. The main reason for this is to protect its image as a newly industrialised country; it does not need to rely on other countries for financial help.

Google provided a donation platform to allow donors to make donations securely. Google partners with the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP), an intermediary organisation that specialises in distributing your donations to local nonprofits that work in the affected region to ensure funds reach those who need them the most.

Google Kerala Donate

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.