Typhoon Jebi Case Study

The 2018 typhoon was the largest to hit Japan in 25 years

Japan sits on the Pacific typhoon belt. This is an area where conditions support the formation of tropical storms. There are six main requirements for tropical cyclogenesis: sufficiently warm sea surface temperatures, atmospheric instability, high humidity in the lower to middle levels of the troposphere, enough Coriolis force to develop a low-pressure centre, a pre-existing low-level focus or disturbance, and low vertical wind shear.

Typhoon Jebi unleashed torrential rain and winds of more than 200km/h (125mps) on the western cities of Kobe, Osaka and Kyoto on Tuesday, 4th September 2018. Jebi was the worst typhoon to hit Japan in 25 years. The storm is considered a category-3 typhoon out of five on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

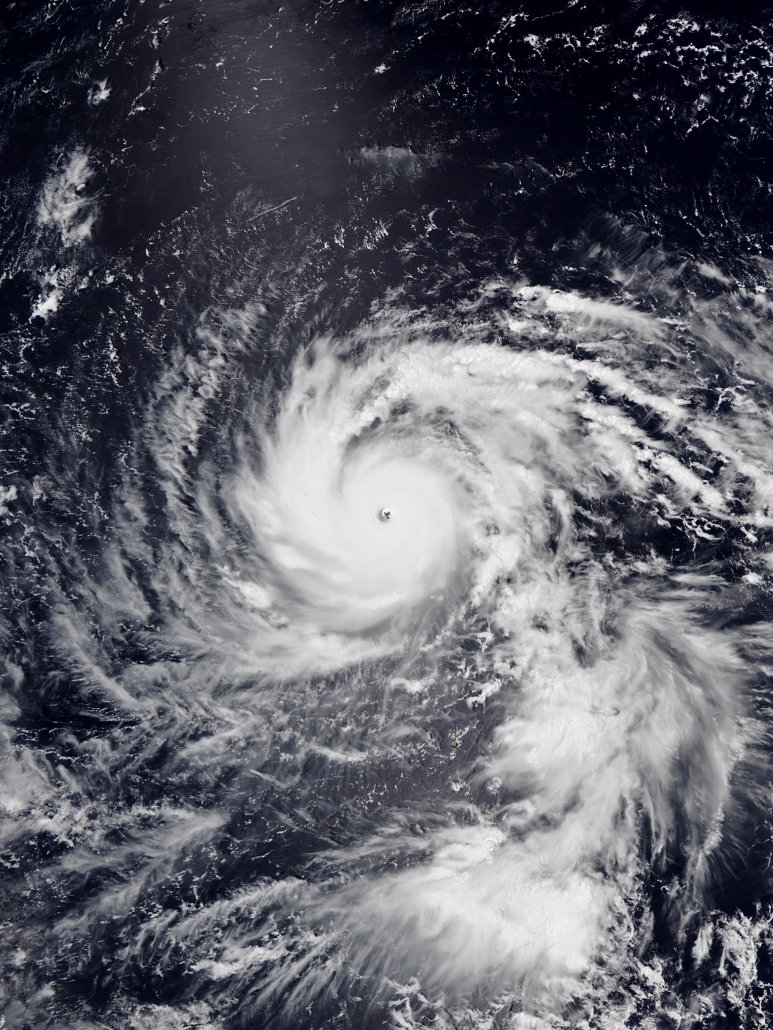

Typhoon Jebi satellite image

The storm inundated the region’s main international airport with water, blowing a tanker into a bridge, disrupting land and air travel and leaving thousands of people stranded.

The storm made landfall on Shikoku, the smallest main island, on Tuesday.

Jebi – whose name means “swallow” in Korean – was briefly considered a super typhoon (see further reading below to find out why).

Typhoons are fairly common in Japan around this time of year; they rarely cause serious damage.

Late on Tuesday, the storm headed into the Sea of Japan.

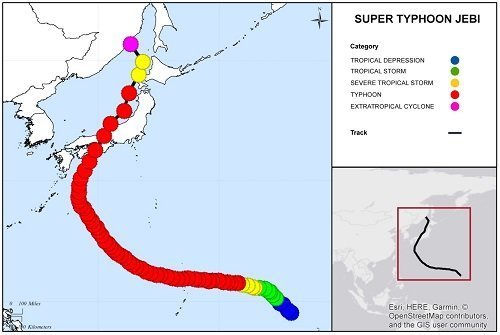

Typhoon Jebi began as an area of low pressure formed close to the Enewetak Atoll in the far western Marshall Islands. Two days later, on the 27th of August, the weather system was upgraded to a tropical depression. The weather system continued to intensify, becoming a tropical storm on the 21st of the season, the following day.

Typhoon #Jebi is making landfall in #Japan, bringing damaging winds, torrential rain, stormy seas and the risk of coastal flooding. There’s recently been a 92 mph gust at Nankishirahama Airport on the south coast of Honshu pic.twitter.com/SBhsEHJIwm

— Met Office (@metoffice) September 4, 2018

After initially moving northwest, Jebi took a more westward track, which intensified as it approached the Northern Mariana Islands. It became a typhoon on the 29th, a Category 3 typhoon on the 30th, and finally a super typhoon on the 31st of August after it passed between the islands of Pagan and Alamagan in the Northern Marianas. Jebi reached its peak intensity, a category five storm with sustained winds estimated at 175 mph by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center, as it made its way into the Philippine Sea. Over the central Philippine Sea, Jebi began to recurve toward the northwest before eventually turning northward as it approached Japan.

The pathway Typhoon Jebi followed – source: http://www.gccapitalideas.com/2018/09/06/super-typhoon-jebi/

As is often the case, the wind shear associated with the change in direction helped weaken Jebi as it approached Japan’s southern part. However, Jebi was the strongest typhoon to make landfall in Japan in 25 years when it came ashore over the eastern end of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, on Tuesday, September 4th at noon, local time. Wind gusts of up to 129 mph were recorded. Jebi then crossed the southern coast of the main island of Honshu near Kobe, bringing heavy rains and high winds to the region.

Typhoon Jebi created havoc that has led to at least 11 deaths, 400 injuries and evacuation advisories for more than a million people.

Waves crashed over sea defences, roof panels were dislodged and blown away by the wind, and high-sided vehicles were lifted onto two wheels and toppled over.

Thousands of air passengers spent the night stranded in an island airport. An estimated 3,000 people were trapped at the terminal of Kansai International Airport, which stands on a human-made island in Osaka Bay. The island was inundated with seawater flooding the runway.

At the other end of a road bridge connecting the airport to the mainland, the Houn Maru, a 2,591-tonne tanker, was reported to have slammed into the side of the structure. The 11 crew were unhurt, but the tanker was damaged.

In central Osaka, the wind sent a 100-metre-tall Ferris wheel into a furious spin, even though its power had been cut off.

About 10cm of rain fell on one part of Kyoto, Japan’s former capital, in an hour. Several people were injured at Kyoto Station when part of a glass ceiling collapsed.

Almost 800 domestic and international flights and ferry and train services were cancelled. Bullet train services between Tokyo and Hiroshima were suspended – but restarted on Wednesday morning – while schools and factories were closed for the day.

Late on Tuesday, 4 September, more than 1.6m households remained without power in Osaka, Kyoto, and four nearby prefectures.

The damage caused by Typhoon Jebi further strained Japan’s recovery budget as the country dealt with several natural disasters during 2018, including flooding and earthquakes.

Winds that in many places gusted to the highest ever recorded in Japan, according to the Japanese Meteorological Agency, left a swathe of damage, with fruit and vegetables, many about to be harvested, hit especially hard.

Before Typhoon Jebi struck, Japan issued more than 1.2 million evacuation notices, none of which were mandatory. Nonetheless, many residents were happy to comply.

Sixteen thousand people spent the night in shelters across 20 prefectures (regions). On Wednesday, 5th September 2018, high-speed boats began transferring stranded passengers from Kansai International Airport to the nearby Kobe airport. This was because the bridge linking the island to the mainland was damaged due to a ship colliding with it.

Roads and public buildings in coastal cities like Osaka are designed to allow excess water and rainfall to flow away efficiently, and advanced coastal defences can reduce the risk of a storm surge.

Perhaps most importantly, the construction of private buildings is strictly controlled to ensure they meet best practices with natural disasters in mind.

Within 24 hours, the number of households without power had been halved to around 530 000.

Hazard preparedness played a significant role in reducing the number of casualties. For example, as Typhoon Jebi approached western parts of Japan, railway operators in the Kansai area acted quickly to inform customers they would halt services to prevent chaos at stations and encourage businesses to let workers stay home to ensure safety.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe cancelled his visits to the southern prefectures of Fukuoka and Kumamoto on Sept. 4 to lead the government’s response to Typhoon Jebi. This followed criticism of the government’s slow response to flooding in July 2018.

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.